The church founded at Leominster, in 660AD, was a Celtic church, a seed planted by a missionary from Lindisfarne, St Edfrith, whose religious heritage lay far to the west on the island of Iona. It was the first great minster to be founded in Herefordshire, pre-dating Hereford Cathedral. Legend has it that Edfrith converted the local King Merewalh to Christianity by translating his troubled dreams. That seems fanciful, but the reality is that Merewalh and his successors were inspired to endow the foundation with an extensive estate, covering the twenty seven parishes which form the modern “team ministry”.

The church founded at Leominster, in 660AD, was a Celtic church, a seed planted by a missionary from Lindisfarne, St Edfrith, whose religious heritage lay far to the west on the island of Iona. It was the first great minster to be founded in Herefordshire, pre-dating Hereford Cathedral. Legend has it that Edfrith converted the local King Merewalh to Christianity by translating his troubled dreams. That seems fanciful, but the reality is that Merewalh and his successors were inspired to endow the foundation with an extensive estate, covering the twenty seven parishes which form the modern “team ministry”.

Much of this area was low lying and marshy, so that Leominster, or Llanllieni in Welsh, was an island. When the precincts of the minster were delineated, the streams to the north and east formed boundaries so that an earth bank was only needed to the south and west. This earthwork can still be seen around the edge of the Grange. The great church was the centre of a complex network of farms and churches which made it wealthy and influential. An important prayer book survives from the Saxon minster, partly written by a woman, and it seems that the monastery had become a nunnery, following the Benedictine rule, by 1100. It was a highly regarded house, but fell victim to the depredations of local warlords, and was “destroyed”.

In 1125, Henry I refounded the monastery at Leominster and gave it to Reading Abbey. As a dependency, it became a priory, not an abbey, and that is the title that has persisted. The ancient church was dedicated to St Peter and St Paul and that dedication has also come down to us today (there was a second church dedicated to St Andrew to the north, near the level crossing).

From the second foundation until the dissolution of the monasteries in the mid-Sixteenth century the estates provided riches to Reading, including the profits from the Ryland sheep, whose wool was the most prized in Britain. At first, the parishioners of the town used the Norman nave attached to the monastic church to the east, but the inevitable conflicts between town and cowl led to the building of the Forbury Chapel in Church street for the use of the parish. This did not satisfy the grandiose ambitions of the burgesses and a new parochial nave to the south of the Norman nave, was consecrated in 1239. Almost a century later, the magnificent south aisle in the Decorated style was added; the Early English porch had to be moved outwards to achieve this. It was to the parochial part of the church that the magnificent west tower and west window were added in the Fifteenth century in a display of the growing wealth and power of the town’s elite.

The monastery was surrendered to the Crown in 1539. The monastic parts were quickly demolished, and the stone, metal and glass sold. In the period of iconoclasm which followed, images of Christ, the Virgin, saints and angels were destroyed in the parish church. Leominster engaged in this destruction with enthusiasm and much of the stained glass, for example, was put into houses in the town. At the end of the Seventeenth century, there was a terrible fire which destroyed the rest of the medieval art in the church, with few exceptions, notably the Wheel of Life wall painting and some of the ancient sculpture.

The church survived the ups and downs of religious life through the Eighteenth and early-Nineteenth centuries. At one point galleries were added, and a great panel with the Royal Arms was painted (now out of sight in the vestry). But, in common with many churches, the declining condition of the fabric combined with a revival of interest in the religious significance of art and music to demand a thorough restoration and reordering of the building. George Gilbert Scott, the preeminent Victorian church architect was engaged, and the interior of the church transformed by the removal of galleries and the building of a new arcade between the south nave and aisle.

The use and furnishing of the church have continued to evolve, and the beautiful St Paul’s Chapel at the east end, and the reordering to make a nave altar and choir stalls closer to the congregation stand out as transforming Sunday worship.

ARCHITECTURE AND FURNINSHINGS

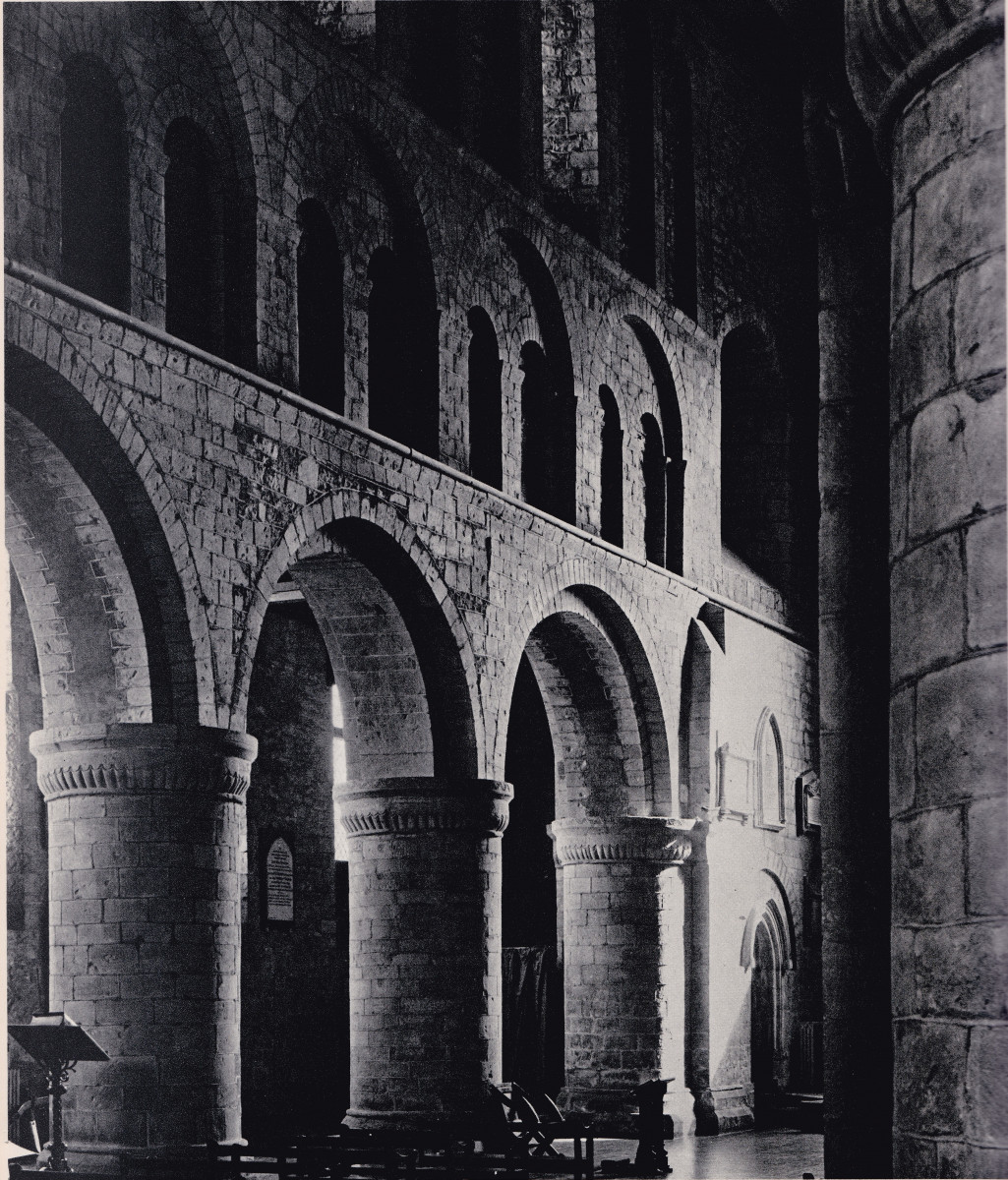

The north Norman nave is the most impressive part of the Priory. Its noble scale and massive round columns supporting round arches are memorable, but it will be noticed that alternate bays have a more solid appearance with a narrow opening, or a lower round arch, which is unusual. These more solid bays were needed to support the original roof, now lost, which was formed from a series of domes. Before the Reformation, the Norman nave ended at a screen to the east, on which ceremonies would be enacted and an image of the crucified Christ would have been displayed. The staircase to reach the top of the screen is still visible in the south nave. The Norman church extended a long way to the east into a chancel surrounded by an aisle from which little chapels radiated. There were also transepts stretching behind the end wall of the south nave and aisle and out into the car park to the north. This was the holy sanctuary where the monastic offices and masses were celebrated, and from which the public were excluded. The present east window in Norman style is modern.

Some important art survives from this early period. High up on the south wall of the Norman nave, faint traces of painted decoration can be seen, and on the capitals of the west doorway (most impressive from outside) are carvings made by the famous Herefordshire School of Romanesque sculpture. The images from c1150 include hawks, lions, men tending vines and Samson and the Lion. At the west end of the north aisle, in the present choir vestry, is a wall painting of c1275 which depicts the Wheel of Life with a circle of roundels showing the six Ages of Man.

There are also interesting furnishings presently in the Norman nave, although the Ducking Stool, is hardly a piece of furniture. The history of the ducking stool is displayed alongside, but it is worth emphasising here that it is a unique object of English social history and, though objectionable, it is not celebrated and cannot be denied. At the east end, on the dais, are 17th century wooden benches, used as communion rails and one of a pair of fine oak communion tables (the twin is in the Lady Chapel) which must have been commissioned soon after the fire of 1699. The iron plough, which is used in Plough Sunday services is also of note - it was owned by a champion ploughman.

There are also interesting furnishings presently in the Norman nave, although the Ducking Stool, is hardly a piece of furniture. The history of the ducking stool is displayed alongside, but it is worth emphasising here that it is a unique object of English social history and, though objectionable, it is not celebrated and cannot be denied. At the east end, on the dais, are 17th century wooden benches, used as communion rails and one of a pair of fine oak communion tables (the twin is in the Lady Chapel) which must have been commissioned soon after the fire of 1699. The iron plough, which is used in Plough Sunday services is also of note - it was owned by a champion ploughman.

In the parish or south nave and the south aisle, galleries and fixed pews were removed in the 1860s and the platforms for pews were made but pews were never provided so that the wooden seats are a rare early example of “flexible seating”. Almost all the furnishings, are post-1860 but there is a gem of unknown origin in the form of the medieval plank chest which presently stands in front of the Lady Chapel screen, and the small font near the nave altar is probably 13th century.

In the 19th century, the art of stained glass was revived, and Leominster is fortunate to have windows by the Kempe workshop:

In the 19th century, the art of stained glass was revived, and Leominster is fortunate to have windows by the Kempe workshop:

East window: The Crucifixion with saints Peter, Mary, John and Benedict, instruments of the Passion and angels is a late work of 1922.

Lady Chapel The south window is a rich piece of 1898 with the Annunciation and Incarnation and Moses with the Burning Bush.

South Aisle The east window of the south aisle shows the Nativity and the annunciation to the shepherds.

The use of the Priory will continue to evolve, but its rich heritage will be respected, and it will remain a building at the heart of the life of Leominster.